A few days ago there was a minor Twitter frenzy, when a poor Texan tourist found himself locked in the Trafalgar branch of Waterstones, after it had closed for the day.

He tweeted: "Hi @waterstones I've been locked inside of your Trafalgar Square bookstore for 2 hours now. Please let me out."

Waterstones replied "Thanks for the tweets today! We'll be back at 9am tomorrow to answer your queries :) Happy reading!"

Fortunately, thanks to the power of social media, he was released within a few hours. If it had been 25 years ago, when I worked at Waterstone's, the poor man would have probably still been there the following morning.

It was a good story, but less unusual than people might think. I've locked people in a bookshop several times and I know that some of my former colleagues have too. It's more easily done than you might think.

On each occasion, we walked around the shop floor shouting that we were closing, then started turning the lights off, beginning at the top floor. This was usually a foolproof way of forcing people downstairs, like moths to the flame, until the only source of light would be the street lighting outside.

But sadly some people failed to take the hint.

One poor man was deaf and didn't hear the annoucement, but I still wonder why the darkness didn't make any impression on him. Another man was foreign and, perhaps, came from a country where unlit, empty shops were the norm.

(Thinking about it now, it was always men who got stuck in the shop)

Another time, some members of the criminal classes deliberately hid in the shop and went to a great deal of effort to open our safe, even making a hole in the wall behind it. They failed. If they'd succeeded, they would have found less than £1000 in cash.

Once we'd twigged that shouting and darkness weren't sufficient clues, we became more vigilant and no further incidents followed.

But to return to the locked Texan, during the Twitter storm, several people remarked how they'd love to be in an empty bookshop at night and I remembered the times when I took advantage of having the key to the shop.

Sometimes it was just enough to be able to browse without being disturbed by anyone. But I also remember dancing on the shop floor at midnight with some friends, playing my favourite tapes on the PA system at full volume and, on one occasion, walking around in my boxer shorts, just because I could.

In another branch, the manager and her staff would often go to the pub until closing time, then return to the shop for a pyjama party, during which more alcohol was consumed until everyone finally collapsed from exhaustion.

I've also heard that a few customer sofas have been the scene of some decidedly non-literary encounters between members of staff.

Of course, none of this could happen today. These days, shops have digital CCTV and sophisticated alarm systems, so dancing in the dark, noctural nudism, midnight couplings and sleepover sessions are no longer an option. Even entering the shop outside trading hours would probably count as gross misconduct. How sad.

On the plus side, if you want to get locked in a bookshop, you can now feel reasonably confident that you won't stumble on any safecrackers, copulating booksellers or midnight bacchanales, so it's probably a good time to try. Just head for an upopular section like poetry or transport and keep your head down.

Good luck.

P.S - Please check the opening hours. An absence of customers and staff is no longer an indication that the shop is actually closed.

Showing posts with label waterstones. Show all posts

Showing posts with label waterstones. Show all posts

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Saturday, October 12, 2013

Back to Waterstones

Yesterday I returned to Waterstones in Piccadilly for the first time in years. The last time I was there, it was to attend a tedious and morally repugnant training course on a thing called IPI, which stood for Individual Performance Improvement. It was a euphemism for 'managing people out of the business' or, more bluntly, getting rid of people without having to pay them any redundancy money.

The word 'sacking' was a complete taboo, naturally.

I found the terminology of Waterstones rather depressing: resource for staff, learnings for lessons, handselling for talking to customers and, worst of all, product for books. In the end, I managed myself out of Waterstones before anyone had the chance to subject me to the full horrors of IPI.

Today, Waterstones is a different place. The company is now back in the hands of real booksellers and the shops look better than ever, with a vastly-improved range and presentation that recalls the good old days of Waterstone's, minus the mess.

I'd travelled to Piccadilly to meet a friend and as it was a little early for the pub, we decided to have tea in the restaurant on the 5th floor.

The view from the restaurant was impressive and the atmosphere was very relaxed compared to the tourist-clogged streets of the West End, but I was slightly put off by an irritating tannoy that kept shouting in a shrill, insect-like voice. What was the point of it?

Then I noticed that it wasn't a tannoy. Sitting at a table by the window, a large woman in her late 50s, with long hair and a tweed poncho, was watching a video on her laptop. She must have turned up the sound to compensate for the noise of people's conversation and the clanging of plates in the kitchen.

People started to look at the woman and at one point I thought a waitress was going to speak to her. But in true London fashion, everyone pretended it wasn't happening. When I decided to take the law into my own hands, she seemed genuinely surprised.

Has it now become socially acceptable to play videos in public places?

As we left the restuarant and reached the top of the staircase, I remembered that this used to be one of the suicide hotspots of London. The winning combination of alarmingly low bannisters and an unhindered 100-foot descent to a solid marble floor exerted a fatal attraction for some and we became used to the emails that read "Waterstones Piccadilly will be closed for the rest of the day."

I was relieved to see that the new management had added perspex screens above the bannisters.

Like me, my friend used to manage bookshops for Ottakar's. She left 12 years ago and now had a successful career in academic publishing, but missed the fun and camaraderie of bookselling. I agreed, but said that we were lucky to have left when we did.

James Daunt's Waterstones seems a much better place than the bad old days of HMV, but the shops feel like the last days of the Byzantine Empire.

Managing Director James Daunt has tried to keep one step ahead of the decline in high street sales by focusing on making Waterstones more profitable. Loss-making stores have been closed, superfluous senior managers have been culled and the expensive head office in Brentford was closed (the slimmed-down management team now work in Waterstones Piccadilly).

But perhaps Daunt's most radical move took place earlier this year, when every manager and assistant manager was asked to reapply for their job. The aim was to reduce the payroll costs (I would guess by something in the region of £4,000,000) and ensure that the remaining managers were proper booksellers.

Sadly, the plan backfired somewhat, as some of the best managers in the company decided to jump ship rather than go through the consulation process. Out of 487 managers, around 200 left.

I met some ex-Waterstones managers at a party last week and the general view was that they felt that it made more sense to take the money and run (there was a relatively attractive redundancy package). I asked why, as I'm sure they would have kept their jobs. Their answer was simple: they felt that there was no future in bookselling.

Several years of declining sales, watching customers use their shops as a showroom for smartphone purchases from Amazon, had convinced these managers that the writing was on the wall. It was time to leave the sinking ship.

But was Waterstones a sinking ship?

In a recent interview, James Daunt asserted that Waterstones would be back in profit within two years. It seemed a grandiose claim, but W H Smith has surprised everyone by producing ever-improving profits in the face of declining sales, thanks to some very astute financial controls.

If Daunt can follow suit, reducing the costs of the business at a level that outpaces the decline in sales, then the chain could survive for years. But if I was a manager in my 30s, I wouldn't take that gamble.

By the time my friend and I left it was dark. We walked in the rain, avoiding the groups of shuffling tourists, until we found a reasonably enticing pub. As we sat drinking our pints of Guinness, we reminisced about the days when we'd go to launch parties, stagger home, sleep for four hours and then go to work.

We were usually indefatigable, although there was one occasion when my staff found me asleep on the office floor after a particularly generous publisher invited us to a cocktail bar.

At the time it was great fun (although my liver probably wouldn't agree) and it never occured to any of us that this world would come to an end. Every year, Ottakar's opened new branches and I assumed that this process of expansion would continue for many years to come.

When I opened my most recent shop, I had no idea that it would be one of the last new bookshops in the UK.

Of course, there are still bookshops, launch parties and author signings, but it is taking place against a backdrop of a relentless decline in year on year sales. Every year, Byzantium gets at little smaller and the Ottoman Empire gets a little larger. Soon, the enemy will be at the gates.

I wonder where it will all end.

The word 'sacking' was a complete taboo, naturally.

I found the terminology of Waterstones rather depressing: resource for staff, learnings for lessons, handselling for talking to customers and, worst of all, product for books. In the end, I managed myself out of Waterstones before anyone had the chance to subject me to the full horrors of IPI.

Today, Waterstones is a different place. The company is now back in the hands of real booksellers and the shops look better than ever, with a vastly-improved range and presentation that recalls the good old days of Waterstone's, minus the mess.

I'd travelled to Piccadilly to meet a friend and as it was a little early for the pub, we decided to have tea in the restaurant on the 5th floor.

The view from the restaurant was impressive and the atmosphere was very relaxed compared to the tourist-clogged streets of the West End, but I was slightly put off by an irritating tannoy that kept shouting in a shrill, insect-like voice. What was the point of it?

Then I noticed that it wasn't a tannoy. Sitting at a table by the window, a large woman in her late 50s, with long hair and a tweed poncho, was watching a video on her laptop. She must have turned up the sound to compensate for the noise of people's conversation and the clanging of plates in the kitchen.

People started to look at the woman and at one point I thought a waitress was going to speak to her. But in true London fashion, everyone pretended it wasn't happening. When I decided to take the law into my own hands, she seemed genuinely surprised.

Has it now become socially acceptable to play videos in public places?

As we left the restuarant and reached the top of the staircase, I remembered that this used to be one of the suicide hotspots of London. The winning combination of alarmingly low bannisters and an unhindered 100-foot descent to a solid marble floor exerted a fatal attraction for some and we became used to the emails that read "Waterstones Piccadilly will be closed for the rest of the day."

I was relieved to see that the new management had added perspex screens above the bannisters.

Like me, my friend used to manage bookshops for Ottakar's. She left 12 years ago and now had a successful career in academic publishing, but missed the fun and camaraderie of bookselling. I agreed, but said that we were lucky to have left when we did.

James Daunt's Waterstones seems a much better place than the bad old days of HMV, but the shops feel like the last days of the Byzantine Empire.

Managing Director James Daunt has tried to keep one step ahead of the decline in high street sales by focusing on making Waterstones more profitable. Loss-making stores have been closed, superfluous senior managers have been culled and the expensive head office in Brentford was closed (the slimmed-down management team now work in Waterstones Piccadilly).

But perhaps Daunt's most radical move took place earlier this year, when every manager and assistant manager was asked to reapply for their job. The aim was to reduce the payroll costs (I would guess by something in the region of £4,000,000) and ensure that the remaining managers were proper booksellers.

Sadly, the plan backfired somewhat, as some of the best managers in the company decided to jump ship rather than go through the consulation process. Out of 487 managers, around 200 left.

I met some ex-Waterstones managers at a party last week and the general view was that they felt that it made more sense to take the money and run (there was a relatively attractive redundancy package). I asked why, as I'm sure they would have kept their jobs. Their answer was simple: they felt that there was no future in bookselling.

Several years of declining sales, watching customers use their shops as a showroom for smartphone purchases from Amazon, had convinced these managers that the writing was on the wall. It was time to leave the sinking ship.

But was Waterstones a sinking ship?

In a recent interview, James Daunt asserted that Waterstones would be back in profit within two years. It seemed a grandiose claim, but W H Smith has surprised everyone by producing ever-improving profits in the face of declining sales, thanks to some very astute financial controls.

If Daunt can follow suit, reducing the costs of the business at a level that outpaces the decline in sales, then the chain could survive for years. But if I was a manager in my 30s, I wouldn't take that gamble.

By the time my friend and I left it was dark. We walked in the rain, avoiding the groups of shuffling tourists, until we found a reasonably enticing pub. As we sat drinking our pints of Guinness, we reminisced about the days when we'd go to launch parties, stagger home, sleep for four hours and then go to work.

We were usually indefatigable, although there was one occasion when my staff found me asleep on the office floor after a particularly generous publisher invited us to a cocktail bar.

At the time it was great fun (although my liver probably wouldn't agree) and it never occured to any of us that this world would come to an end. Every year, Ottakar's opened new branches and I assumed that this process of expansion would continue for many years to come.

When I opened my most recent shop, I had no idea that it would be one of the last new bookshops in the UK.

Of course, there are still bookshops, launch parties and author signings, but it is taking place against a backdrop of a relentless decline in year on year sales. Every year, Byzantium gets at little smaller and the Ottoman Empire gets a little larger. Soon, the enemy will be at the gates.

I wonder where it will all end.

Monday, January 02, 2012

Last Year in the Book Trade

As far as the book trade is concerned, I think most people would agree that it was the year of the Kindle, with over a million sold per week in December. HarperCollins alone sold 100,000 ebooks on Christmas Day.

As far as the book trade is concerned, I think most people would agree that it was the year of the Kindle, with over a million sold per week in December. HarperCollins alone sold 100,000 ebooks on Christmas Day.This time last year I was firmly in the anti-Kindle camp and wrote several posts extolling the virtues of the printed page over the soulless, grey world of ebooks. But I protested too much and one blogger very astutely commented that I was actually "on the verge of Kindledom".

I finally gave in during March, swayed by the comments made by fellow bloggers and I have to say, I love my Kindle. It's convenient (my nearest proper bookshop is eight miles away), doesn't clutter up my shelves with books I'll never read again and gives me the chance the try sample chapters before I commit to buying the books.

But there's a dark side to all of this. The Kindle also threatens many booksellers with extinction and could make it harder for authors to earn a living wage from their writing, so I'm in the process of rethinking how I buy books. Particularly after this Facebook discussion that took place a couple of days ago (I won't name the author, as she hasn't given me permission to quote):

Reader 1 -Also love my Kindle and am a sucker for an amazon bargain (sorry). Can't beat the personal service of the 7s bookshop though... Is the publishing world doing anything to support authors? Surely no incentive to write (and I'm aware noone is in it for the money) means no wares to sell?

Author - @Reader 1 - 'Is the publishing world doing anything to support authors?' There is a short answer to this. No. Having been an author for ten years and knowing that my books have been appreciated by thousands I am now forced to consider writing a hobby as I could earn more working on a supermarket check out or sweeping the streets. x

Reader 2 - I'm buying ebooks for an average of £5 each. How much of this is going to the author?

Author - @Reader 2 - this is a good question. For the two of my books that have earned out the advance - if you buy it for £5 I believe I may get as much as about 0.20p (but I have to check this) For the two that have not earned out the advance I get nothing. For the 0.99p purchace of Steve's above the author may - if they are lucky and have earned out - get about 0.5p. But I may be exaggerating the payment to the author wildly here. I always encourage my readers to buy their books from bookshops to keep the bookshops open.

Reader 2 - I'm really shocked. I was always under the impression that authors received 10% of the rrp, with the burden of any discounts shouldered by the publisher and retailer. What's the best thing we can do to support writers?

Author - @Reader 2 - no the author gets 10% of whatever the book is sold at... after (and if) the advance is earned out (and it's only earned out by a payment at 10 % of whatever the book is sold at) and then after that the agent takes 15% so if people like Steve buy books at 0.99p ... The best thing you can do to support an author is to buy the book from a bookshop at the price that is on the cover. Likewise on Kindle if you pay full price for the download then the author may eventually get a small payment.

The controversy over the 'agency model' (and you can read a full explanation here if you're interested) will continue to rage in 2012. Like a lot of readers, I like cheap books, but not at the authors' expense.

The other big event of 2011 was the rescue of Waterstone's from the edge of oblivion. For people outside the UK, I should explain that it's Britain's largest specialist chain bookseller and for ten years, was run by a succession of 'retailers' (i.e. people who thought that selling books was no different from selling shoes or CDs) who almost destroyed the business. Waterstone's is now in private ownership, freed from the tyranny of short-termism, with a real bookseller at the helm for the first time in years.

However, although things are now looking more positive, I can't help feeling that it's still too late for Waterstone's and that MD James Daunt is merely a Alexander Kerensky/Shapour Bakhtiar figure, unable to stop the tide of history. I may be wrong. Perhaps James Daunt can cure Waterstone's, but I suspect that palliative care is the most he can provide.

As for the literary highlights of 2011, I'll leave that to the many other bloggers - John Self, Gaskella and company - who are highly accomplished book reviewers. However, I will mention one first novel which, I felt, didn't receive the press attention it deserved - 'Wall of Days' by Alastair Bruce -in spite of being picked by Amazon in its 'Rising Stars' promotion.

As for the literary highlights of 2011, I'll leave that to the many other bloggers - John Self, Gaskella and company - who are highly accomplished book reviewers. However, I will mention one first novel which, I felt, didn't receive the press attention it deserved - 'Wall of Days' by Alastair Bruce -in spite of being picked by Amazon in its 'Rising Stars' promotion. If I try to explain the plot I might put you off, so it's probably better to simply include this link to the first few pages. If you like bald, understated prose, like Cormac McCarthy or M. J. Hyland, where devastating truths are hidden beneath mundane recollections, then I can highly recommend this magical novel.

If I try to explain the plot I might put you off, so it's probably better to simply include this link to the first few pages. If you like bald, understated prose, like Cormac McCarthy or M. J. Hyland, where devastating truths are hidden beneath mundane recollections, then I can highly recommend this magical novel.Another reason why Wall of Days struck a chord is that for several years, I'd had a novel brewing in my head that had a very similar beginning. As soon as I began reading the first page, I felt a huge sense of relief that someone had written the novel for me and done a much better job of it. I can now hit the pillow without any more recurring images of grey skies and tussock grass.

Finally, I must mention one other book: Vasily Grossman's 'Life and Fate', which is belatedly being acknowledged as one of the great novels of the 20th century, comparable to War and Peace in its scope and ambition. Although the English translation appeared a few years ago, it wasn't until 2011 that Grossman's epic began to receive the recognition it deserved.

It took me over a month to read Life and Fate, but I would happily read it all over again tomorrow.

Finally, I'd like to wish anyone who reads 'the Age of Uncertainty' a Happy New Year. After a number of challenges and upheavals last year, the blog began to run out of steam towards the end of the year, as I was exhausted by family difficulties and preoccupied with setting up my own bookselling business.

Perhaps, after five years, this blog has reached a natural end. But it's possible that once I have new sources of stock, there will be other stories to tell. I really enjoy sharing the strange fragments of lost lives that seem to come my way and hope that there will be more to come.

We shall see.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Grey is the Colour of Hope

I popped into the Colchester branch of Waterstone's this morning to see if the recent change of ownership had made any difference. At first, it looked exactly the same, but then I noticed that the shelves seemed much fuller and there were very few annoying posters with banal bylines.

I popped into the Colchester branch of Waterstone's this morning to see if the recent change of ownership had made any difference. At first, it looked exactly the same, but then I noticed that the shelves seemed much fuller and there were very few annoying posters with banal bylines.

It felt more like a bookshop.

I suppose it was unrealistic to expect anything dramatic; after all, James Daunt's only been in the job for a couple of months. I shall have to go back later in the year.

I must have been scrutinising the shop a little too conspicuously, as a nervous-looking assistant made a beeline for me and asked if I needed any help. I think they thought that I was a mystery shopper. I was tempted to play along and start asking ridiculous question, but thought better of it.

I've never been a mystery shopper, but I used to pretend to be a restaurant critic. I'd dress smartly and turn up with a small clipboard, pretending to surreptitiously take notes which I made a great play of concealing every time a waiter approached. After ordering, I'd inspect the loos and ensure that I 'accidentally' walked into the kitchen, scanning the surfaces for any signs of dirt. As the evening progressed the waiters became increasingly attentive and at some point, I'd invariably end up getting at least one free drink (a decent one, not a thimblefull of Bailey's).

At the end of the visit, the waiters would wait by the door and, with anxious smiles, ask me if I'd had an enjoyable evening. I'd nod knowingly and reply "A very enjoyable evening indeed." Their relief was palpable.

Was that wrong? I never actually claimed to be anything I wasn't; I just let people infer it from my behaviour. Either way, it was good fun.

But I digress. Returning to Waterstone's, the shop looked good and it was packed, so perhaps there's still some hope for the high street bookshop. I hope so. The way everyone is talking about the 'Kindle', it feels as if the question about the demise of bricks and mortar bookselling is not if, but when.

However, I have uncovered evidence of a failed attempt at Kindle-style reading from the 1940s:

This book was published during the Second World War and although it looks perfectly ordinary on the outside, the contents reveal a bold new initiative in the publishing world. Black on grey:

This book was published during the Second World War and although it looks perfectly ordinary on the outside, the contents reveal a bold new initiative in the publishing world. Black on grey:

"Black text on a grey background? It'll never work, Carstairs. It looks damnably awful!"

"Black text on a grey background? It'll never work, Carstairs. It looks damnably awful!"

And that was the end of that. The book industry had to wait another 65 years before the Kindle made grey backgrounds acceptable.

But sometimes grey can be good:

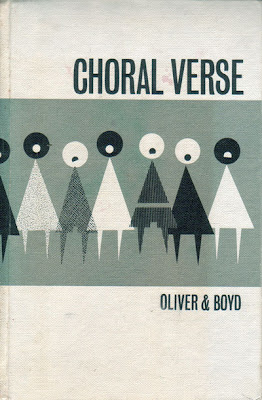

I love cover designs like this from the 1960s, which have an elegance, simplicity and wit that has never been surpassed. In this post, Richard from Grey Area posted a comment that pointed out how much work went into creating such seemingly effortless designs.

I love cover designs like this from the 1960s, which have an elegance, simplicity and wit that has never been surpassed. In this post, Richard from Grey Area posted a comment that pointed out how much work went into creating such seemingly effortless designs.

Just a few years before 'Choral Verse', dustjackets like this were the norm:

This is a sex education book for young people from the late 1950s. I'm no expert on these matters, but I would have thought that the first thing they could do is take their raincoats off.

This is a sex education book for young people from the late 1950s. I'm no expert on these matters, but I would have thought that the first thing they could do is take their raincoats off.

But I mustn't mock. It's actually quite a good book, full of dangerous, radical ideas, like trying to see things from the woman's perspective.

I'm not sure if these women needed any advice with delicate matters:

In the second picture, the urban sophisticate deals with a group of 'brigands' with barbed wit and condescension. I've tried that approach too, but with more mixed results.

In the second picture, the urban sophisticate deals with a group of 'brigands' with barbed wit and condescension. I've tried that approach too, but with more mixed results.

There's something very appealing about the demi-monde of the period between the wars, but I'm also attracted to the innocence of children's book illustrations from the mid-20th century:

I expect that these children were called Peter, Joan, Colin and Kenneth and their parents didn't mind them sitting on the edge of tall buildings in the dark, because they were too busy getting 'tight' at the local yacht club.

I expect that these children were called Peter, Joan, Colin and Kenneth and their parents didn't mind them sitting on the edge of tall buildings in the dark, because they were too busy getting 'tight' at the local yacht club.

Finally, four photos that turned up at work last week:

A very moody shot. Perhaps it's all a little too English for this gentleman.

The sporting Scotsmen theme continues with this appealing portrait of a young boy.

The sporting Scotsmen theme continues with this appealing portrait of a young boy.

This couple are also from Scotland, but there's no evidence of any sporting activity.

This couple are also from Scotland, but there's no evidence of any sporting activity.

Finally, a slightly disturbing portrait of Father Christmas:

I'm not sure what effect this Santa would have had on the young visitors to his grotto, but I'm sure that it can't have been as bad as the New York department store that had a sign outside which promised: 'FIVE SANTAS. NO WAITING.'

I'm not sure what effect this Santa would have had on the young visitors to his grotto, but I'm sure that it can't have been as bad as the New York department store that had a sign outside which promised: 'FIVE SANTAS. NO WAITING.'

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

How I Would Save Waterstone's*

Last week the shareholders of HMV reached an almost unanimous decision to approve the sale of its Waterstone’s bookshop chain to the Russian billionaire Alexander Mamut. Today, the business officially changed hands and bookseller James Daunt took over as MD.

Last week the shareholders of HMV reached an almost unanimous decision to approve the sale of its Waterstone’s bookshop chain to the Russian billionaire Alexander Mamut. Today, the business officially changed hands and bookseller James Daunt took over as MD.This is great news for everyone in the publishing industry, not to mention readers who value specialist booksellers with large stockholdings.

Also, on a personal note, as it is almost five years to the day since the bookshop chain I worked for was bought by HMV, it has been hard not to to feel a certain schadenfreude at the demise of those people who thought that bookselling was no different from any other area of retail. I hope that there will be no need for the word ‘product’ in James Daunt’s Waterstone’s.

But before we put out the flags, a word of caution. HMV may have mismanaged Waterstone's for over a decade, but can a change ot ownership make that much of a difference in a market that appears to be undergoing an irreversible transformation?

However good Alexander Mamut and James Daunt are, they still might fail.

Before we look at the uphill struggle that faces James Daunt, lets focus on the positives:

- In spite of Amazon and the supermarkets, Waterstone’s is still a profitable business

- In 2010, its market share was just under 30% of total book sales

- It frequently achieves high scores in customer satisfaction surveys

- It is the only large specialist bookshop chain in Britain

- Publishers want Waterstone's to survive

But the reality is that Waterstone's is dying, albeit very slowly. The sales have been slowly shrinking for over five years and many shops are now making a loss, including the 'flagship' Piccadilly store. Several years of negative growth have produced an entrenched mentality in the senior management and rather than trying to increase sales (or 'grow' sales, as they now say), the emphasis is on reducing costs: the beginning of the end.**

The main management failures of Waterstone's are as follows:

- They failed to establish an strong internet presence in the mid-90s and after a half-hearted attempt, let Amazon fulfill its online orders until 2006 - a move that rivals Decca's decision not to sign the Beatles

- They became obsessed with wooing the mass market at the expense of their traditional market of 'heavy book buyers'

- They recruited too many middle managers from other areas of retail, who knew nothing about books and came from businesses that valued compliance and uniformity over creativity and passion, resulting in a chain of bland, unexciting bookshops

- The whole business was dominated by a counter-intuitive stock control system that looked and felt like a second rate MS-DOS program from 1989

- They reacted to changes in the book trade, rather than anticipating them

One of the most salutary (I know this word has been out of fashion since the 1870s, but I like it) lessons I learned in the book trade was when Waterstone's took over Ottakar's, rebranding every shop in the chain. For me, it was a cataclysmic event. For my customers, it was just another day. Very few of them even noticed the huge new black sign over the door.

Getting the book buying public excited about Waterstone's again will be a huge challenge.

To make things worse, the high street is going into meltdown. Long established brands like Mothercare, Habitat, Thorntons and TJ Hughes are either going into administration or slashing the number of stores, as customers increasingly migrate to the internet.

It's not a good time to work in high street retailing.

In an ideal world, James Daunt would have a few months to get his head around the business before coming up with a plan to save the chain. Unfortunately, time is a luxury James Daunt doesn't have. The crucial Christmas promotions will have to be signed off almost immediately.

On the one hand I don't envy James Daunt, but on the other, this is a fantastic opportunity. The death of Waterstone's needn't be inevitable. Other chains have suprised their detractors by reversing their fortunes and it's possible that James Daunt and Alexander Mamut may go down in posterity as the men who saved Britain's last bookshop chain.

On the one hand I don't envy James Daunt, but on the other, this is a fantastic opportunity. The death of Waterstone's needn't be inevitable. Other chains have suprised their detractors by reversing their fortunes and it's possible that James Daunt and Alexander Mamut may go down in posterity as the men who saved Britain's last bookshop chain.But how?

If I was sitting in James Daunt's chair next Monday, these would be my priorities:

1. Increase the stockholding.

There was a time when you could go into most branches of Waterstone's and expect to find all of the backlist of authors like Ian McEwan or William Boyd. Not any more. Without a decent range, Waterstone's is finished. Of course, keeping a large range of slow-moving backlist titles is expensive, but if publishers are really serious about supporting Waterstone's, they should provide the stock under more favourable terms. Surely it's in the publishers' interest to have their books in shops rather than in a warehouse?

If customers can once again feel confident that they can find the book they want today (at a competitive price), they'll be less likely to automatically default to Amazon.

2. End the blandness.

Whether you're looking at the homepage of www.waterstones.com or gazing at a shop window, the overall impression is one of blandness. Dull, safe posters with insipid, dumbed-down bylines and predictable 3 for 2 promotions that have the same titles in month after month - that's the modern Waterstone's. In Ottakar's, shops competed with each other to come up with the quirkiest, most eye-catching windows. In Waterstone's, compliance has been valued over creativity.

Waterstone's branches need to make their shops as exciting as the books: eccentric, unpredictable, magical places, buzzing with energy, otherwise what's the point of going there?

As for the website, it should be a bibliophile's paradise, with videos of author interviews, YouTube clips of signing sessions and a vast archive of author information. At Ottakar's I was on the editorial committee of an award-winning fiction microsite and we produced hundreds of author biographies. I presume that Waterstone's now own that data, so why isn't it being used on their website?

3. Embrace the e-book.

As with the internet, Waterstone's made a half-hearted attempt at competing with Amazon and squandered a vital opportunity to get on the digital bandwagon. The game isn't over yet. Thousands of backlist titles have yet to be digitised and if Waterstone's can come up with a genuinely competitive alternative to the Kindle, they may be able to stop their shops becoming showrooms for Amazon.

4. Put staff morale at the top of the agenda.

The working culture in Waterstone's has been awful. An obsession with compliance has produced a climate of fear, where disciplinary action is routinely used as a motivational tool. When shops are earmarked for closure, staff often find out from the trade press before they receive any communication from the senior management.

The key to Waterstone's recovery is the enthusiasm and passion of its booksellers. But it will be hard to improve staff morale if the store managers are stuck in the back office for most of the day, completing one spreadsheet and after another. The excessive bureacracy should be trimmed down so that managers can spend more time selling books.

Staff morale in James Daunt's own chain is good, by all accounts. I hope that he can persuade some of the more abrasive characters in Waterstone's middle management to change their approach.

5. Give power back to the shops.

When I worked on a few projects for Ottakar's head office, I had access to the company's sales data and used to love analysing the sales performance of particular titles in different shops. Why did book X sell 57 copies in one shop, but only 4 in another, when both stores had a similar turnover? Sometimes it was because one shop had sold out, but more often than not it was because the local market was very different.

There has been a lot of talk in Waterstone's about responding to the local market, but when I walk in the front door, all I see is a bland, one-size-fits all approach. Each shop should have a unique offering that reflects the passion and knowledge of its staff, along with a strong awareness of the local customers.

6. Ditch the new Waterstone's logo:

Alright, number six isn't essential (I know some people even prefer the new drooping breasts logo to the traditional, angular W). The main thing is shops with more books, and a range and pricing that reflects the local market.

Alright, number six isn't essential (I know some people even prefer the new drooping breasts logo to the traditional, angular W). The main thing is shops with more books, and a range and pricing that reflects the local market.I could go on. I haven't even touched on the thorny issue of closing unprofitable shops, fixing or scrapping the central distribution hub, introducing a half-decent EPOS system or paying people more money. But that's enough to be going on with.

You may completely disagree with me (indeed I hope some people do, as I like a good debate). Perhaps Waterstone's would be even worse off today if it hadn't been run on strict retail lines. I don't know. All I can say is that as an Amazon customer, the main thing that would get me back into Waterstone's is a quirky, exciting range. However good Amazon is, you can't beat real browsing.

I wish Alexander Mamut and James Daunt the best of luck (and God knows, they'll need it). If they can bring Waterstone's back from the brink of extinction, to the point where it is a viable business with a future, both readers and publishers will owe them a huge debt.***

* The title should really be 'How I Would Go About Saving Waterstone's' (I wouldn't be arrogant enough to assume that I have the answers), but I went for the punchier option.

** Since writing this post, it has been announced that during its year under Dominic Myers, Waterstone's increased its profit by £6.7 million. This is a great achievement, but doesn't alter the fact that unless the business reverses the decline in sales (last year's were nearly 4% down on the previous year), its days are numbered. Also, let's not forget that during Myers tenure, Waterstone's sales received a temporary boost from the demise of Borders.

*** Two years on, the chain appears to be trying to replicate the success of Daunt's by turning Waterstones into a collection of mini-chains, or 'clusters'. Unprofitable stores are being closed the moment their leases expire, while some of the more successful shops have undergone refits. There has been a cull of middle and senior managers. As for ebooks, after looking at all the alternatives, James Daunt reluctantly decided to embrace the Kindle rather than waste time and money on a white elephant.

I agree with most of Daunt's decisions, but I'm not convinced by his new buying structure. I would have given the shops complete autonomy, but perhaps James Daunt felt that after the HMV years, there weren't enough real booksellers around to take that risk.

The chain is now in a race against time to contract to a sustainable level at a rate that keeps pace with the declining year on year sales. I suspect that they are being outpaced by the migration of sales to Amazon's Kindle offer.

****Three years on, it looks as if Daunt has done it. Ebook sales have levelled out and Waterstones looks set to break even for the first time in years. The medicine has been bitter, for some at least, with many redundancies and the loss of some very talented people, but it was an ineluctable fact that the costs of the business were too high. I remained sceptical about Waterstones until I saw its new branch in Lewes, which is one of the best bookshops I've ever seen.

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

A Dull Post About the Book Industry

Every time I read the trade press, there seems to be yet another story about the growth of e-books. Yesterday alone, the Bookseller published two stories that have huge implications for everyone in the book trade.

The first article covered the 'World e-Reading Congress' in London, where Ian Hudson, the deputy chairman of Random House, announced that their e-book sales had increased tenfold in the last year. Hudson predicted that e-book sales "could exceed 8% of trade publishers' sales in 2011, and could reach 15% next year".

This is interesting, because on the one hand it demonstrates how quickly e-books are growing, but on the other it is a timely reminder that they still account for less than 10% of book sales. If you just listened to Amazon, you could be forgiven for thinking that it was nearer 50%.

The other story that the Bookseller published yesterday is also potentially very significant. Literary über-agent Ed Victor has established a new e-book and print-on-demand imprint, which will initially concentrate on making out of print titles available in a digital format. This may not appear to be earth-shattering news, but it shows that the line between agent and publisher may become increasingly blurred in the future.

So where does that leave the traditional high street bookshop? On they face of it, they seem doomed. E-book sales are growing exponentially, particularly in the more 'disposable' genres like crime fiction (over a third of the latest Jo Nesbø novel's sales were digital).

But although digital publishing may appear to possess the inexorable gravitational pull of a black hole, there are other genres that are far more resistant. For example, this:

I read 'Mr Wonderful' recently after a month in the Kindleverse and fell in love with the paper book all over again.

I read 'Mr Wonderful' recently after a month in the Kindleverse and fell in love with the paper book all over again.

These comic strips are all available online and I'm sure that they'd be quite easy to read on an iPad, but it would be a very poor substitute for this beautifully-produced hardback, with its thick, sturdy pages, brightly-coloured illustrations and wonderfully absurd dimensions (fully opened, it measures 21" by 6").

These comic strips are all available online and I'm sure that they'd be quite easy to read on an iPad, but it would be a very poor substitute for this beautifully-produced hardback, with its thick, sturdy pages, brightly-coloured illustrations and wonderfully absurd dimensions (fully opened, it measures 21" by 6").

I'm not suggesting that bookshops will be saved by bunging a few graphic novels on the front table, but if they are going to survive they need to reduce their dependence on paperback bestsellers and concentrate on genres where the book itself becomes a desirable object. It is this approach that has enabled 'high end' booksellers like Daunt Books to survive, selling hardbacks to people who are looking for quality rather than saving money.

It will be interesting to see what the new owner of Waterstone's does with the chain. At the moment, HMV are locked in negotiations with the Russian billionaire Alexander Mamut. HMV want £70,000,000 for Waterstone's - a sum they desperately need if they are to avoid going into administration in July - and gave Mamut a deadline of April 20th to close the deal.

But with each week, HMV's hand becomes weaker. Their share price is now around 10p and Waterstone's latest value is estimated to be nearer £35,000,000, so I suspect that Mr Mamut is quite rightly driving a hard bargain. Why should he pay over the odds for a 300-branch chain that includes a number a loss-making shops when he could hang on for a few weeks and pick off the most profitable shops?

I hope that both parties are able to reach an agreement before HMV Group collapses, for everyone's sake. Aside from the fact that several thousand jobs are at stake, the publishing industry needs a showcase for its titles and the large, range-holding specialist bookseller is still the best option.

I apologise if that was a very dull post. To make up for it, here is a chimpanzee on a skateboard:

The first article covered the 'World e-Reading Congress' in London, where Ian Hudson, the deputy chairman of Random House, announced that their e-book sales had increased tenfold in the last year. Hudson predicted that e-book sales "could exceed 8% of trade publishers' sales in 2011, and could reach 15% next year".

This is interesting, because on the one hand it demonstrates how quickly e-books are growing, but on the other it is a timely reminder that they still account for less than 10% of book sales. If you just listened to Amazon, you could be forgiven for thinking that it was nearer 50%.

The other story that the Bookseller published yesterday is also potentially very significant. Literary über-agent Ed Victor has established a new e-book and print-on-demand imprint, which will initially concentrate on making out of print titles available in a digital format. This may not appear to be earth-shattering news, but it shows that the line between agent and publisher may become increasingly blurred in the future.

So where does that leave the traditional high street bookshop? On they face of it, they seem doomed. E-book sales are growing exponentially, particularly in the more 'disposable' genres like crime fiction (over a third of the latest Jo Nesbø novel's sales were digital).

But although digital publishing may appear to possess the inexorable gravitational pull of a black hole, there are other genres that are far more resistant. For example, this:

I read 'Mr Wonderful' recently after a month in the Kindleverse and fell in love with the paper book all over again.

I read 'Mr Wonderful' recently after a month in the Kindleverse and fell in love with the paper book all over again. These comic strips are all available online and I'm sure that they'd be quite easy to read on an iPad, but it would be a very poor substitute for this beautifully-produced hardback, with its thick, sturdy pages, brightly-coloured illustrations and wonderfully absurd dimensions (fully opened, it measures 21" by 6").

These comic strips are all available online and I'm sure that they'd be quite easy to read on an iPad, but it would be a very poor substitute for this beautifully-produced hardback, with its thick, sturdy pages, brightly-coloured illustrations and wonderfully absurd dimensions (fully opened, it measures 21" by 6").I'm not suggesting that bookshops will be saved by bunging a few graphic novels on the front table, but if they are going to survive they need to reduce their dependence on paperback bestsellers and concentrate on genres where the book itself becomes a desirable object. It is this approach that has enabled 'high end' booksellers like Daunt Books to survive, selling hardbacks to people who are looking for quality rather than saving money.

It will be interesting to see what the new owner of Waterstone's does with the chain. At the moment, HMV are locked in negotiations with the Russian billionaire Alexander Mamut. HMV want £70,000,000 for Waterstone's - a sum they desperately need if they are to avoid going into administration in July - and gave Mamut a deadline of April 20th to close the deal.

But with each week, HMV's hand becomes weaker. Their share price is now around 10p and Waterstone's latest value is estimated to be nearer £35,000,000, so I suspect that Mr Mamut is quite rightly driving a hard bargain. Why should he pay over the odds for a 300-branch chain that includes a number a loss-making shops when he could hang on for a few weeks and pick off the most profitable shops?

I hope that both parties are able to reach an agreement before HMV Group collapses, for everyone's sake. Aside from the fact that several thousand jobs are at stake, the publishing industry needs a showcase for its titles and the large, range-holding specialist bookseller is still the best option.

I apologise if that was a very dull post. To make up for it, here is a chimpanzee on a skateboard:

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Everything Must Go

Warning! Unless you're particularly interested in the book trade, this is a long, dull post. If you are particularly interested in the book trade, then you probably already know this...

I remember visiting the first UK branch of Borders, back in the late 90s and thinking that I had seen the future.

I remember visiting the first UK branch of Borders, back in the late 90s and thinking that I had seen the future.

Compared to the average Waterstone's, it was bright and airy, with an exciting range of products (I was particularly impressed by the listening posts for CDs). The buzzword in those days was "lifestyle" and the whole ethos of Borders was to create a place where people could "hang out", meeting friends for a coffee, going to a poetry reading or listening to the latest World Music CDs.

A bit like being in an episode of "Friends".

Like most people, I had no idea that I was watching a firework in its final stage, releasing one last spectacular volley of flares. The new Borders store turned out to be one of the last examples of a type of retailing - large stores with huge stockholdings - that would shortly become an anachronism. Once broadband was introduced, internet shopping quickly reached the tipping point and those lovely CD listening posts suddenly seemed ridiculously antiquated.

I was completely wrong about Borders, but I was right about the internet. In 1997, during a drink with a senior figure in Ottakar's (not James Heneage, I hasten to add), I said that it was imperative that we launched an internet site as quickly as possible. He snorted and took great delight in telling me that only 1.5% of the population shopped online and that the figure would only change slowly over time, as most people still weren't comfortable with computers. I wish we'd bet money on it.

Over a decade later, the book chains all appear to be on the brink of collapse. In the USA, Borders are about to go bankrupt and whilst some commentators have blamed years of mismanagement, the truth is that they have merely accelerated the chain's inevitable demise.

Barnes and Noble had a strong management team and embraced the digital age, but it still wasn't enough. Recently Leonard Riggio, the founder of Barnes and Noble, joked "Sometimes I want to shoot myself in the morning."

On this side of the Atlantic, British Bookshops have just gone bust and the management team of Waterstone's have been congratulating themselves for only losing 0.4% in last year's like for like sales.

On this side of the Atlantic, British Bookshops have just gone bust and the management team of Waterstone's have been congratulating themselves for only losing 0.4% in last year's like for like sales.

Given the overall decline in high street sales, -0.4% looks quite promising - certainly much better than its ailing parent company, HMV. But considering that Borders UK ceased trading at the beginning of 2010, it's a pretty dismal result. Waterstone's should have grabbed enough of the Borders market share to come up with some positive figures.

Now that Waterstone's is the last man standing out of the high street bookselling chains, it can only survive by closing its loss-making stores (of which there are a growing number). 20 have already been ear-marked, but I suspect this is only the tip of the iceberg (particularly if HMV are forced to sell the chain).

It's not all bad news for Waterstone's. They still have a significant share of the UK market and there is a core of thriving, profitable stores that have many years left in them if they can free themselves from the shackles of HMV and return to their roots. But overall, I can't help feeling that the age of the chain booksellers was just a brief interlude in the long history of bookselling.

In an article I read recently, someone neatly summed-up the problems facing the bookseller:

The Seven Deadly Paradoxes of Bookselling:

1. The better the bookseller and the more representative their stock, the less chance they have of selling it.

2. The harder a book is to sell, the smaller is their reward for selling it.

3. (The converse, which is more deadly than it first appears.) The easier the book to sell, the greater the reward.

4. The sooner they sell their stock, the longer they must wait before they can replace it on the same terms.

5. In buying the season's new books for stock they must recognize at sight and sometimes at the sight of the jacket only - the merits of their contents.

6. Readers are increasing; purchases are dwindling.

7. The window is their most valuable, and almost their only, advertisement; to be effective it must be in the main part of the town. Few can afford that position.

You may be surprised to learn that these words were written 75 years ago, by Basil Blackwell in a title called "The Book World - a New Survey". Conditions may have changed since 1935 (in Blackwell's day, the enemy was the public library), but the basic principles are the same: sales can rise or fall; rents only go up.

Until recently, it looked as if it was a straightforward battle, with the high street chains losing a war of attrition against the supermarkets and internet booksellers. But just as we were adjusting to the new bookselling landscape, the Kindle suddenly appeared on the scene, shortly followed by the Sony e-Reader.

A couple of years ago I was congratulating myself for swapping high street bookselling for the internet. Little did I know how soon the goalposts were going to move again.

A couple of years ago I was congratulating myself for swapping high street bookselling for the internet. Little did I know how soon the goalposts were going to move again.

Keen to reduce their warehousing costs and stay one step ahead of the competition, Amazon have been aggressively promoting the Kindle. When e-books started to appear on Amazon's bestseller charts, they were accused of manipulating the figures to stimulate demand. But according to Jeff Bezos, millions of people now own Kindles and the demand is growing by the day, with Amazon selling around three in every four e-books.

In the UK alone, it is estimated that several hundred thousand people received Kindles for Christmas, so the tipping point has definitely been reached, but where does that leave the rest of the book trade?

This post is all ready far too long, so I'll be brief. Here are, in my opinion, the main issues facing the book trade today:

BREAKING NEWS... In the three days since I posted this, Borders are trying to negotiate a $500,000,000 refinacing package and Amazon have announced that Kindle sales are now only 20% lower than their paperback sales. Also Waterstone's have asked publishers to reduce scale-down the new title orders and their head of e-commerce has resigned.

I remember visiting the first UK branch of Borders, back in the late 90s and thinking that I had seen the future.

I remember visiting the first UK branch of Borders, back in the late 90s and thinking that I had seen the future.Compared to the average Waterstone's, it was bright and airy, with an exciting range of products (I was particularly impressed by the listening posts for CDs). The buzzword in those days was "lifestyle" and the whole ethos of Borders was to create a place where people could "hang out", meeting friends for a coffee, going to a poetry reading or listening to the latest World Music CDs.

A bit like being in an episode of "Friends".

Like most people, I had no idea that I was watching a firework in its final stage, releasing one last spectacular volley of flares. The new Borders store turned out to be one of the last examples of a type of retailing - large stores with huge stockholdings - that would shortly become an anachronism. Once broadband was introduced, internet shopping quickly reached the tipping point and those lovely CD listening posts suddenly seemed ridiculously antiquated.

I was completely wrong about Borders, but I was right about the internet. In 1997, during a drink with a senior figure in Ottakar's (not James Heneage, I hasten to add), I said that it was imperative that we launched an internet site as quickly as possible. He snorted and took great delight in telling me that only 1.5% of the population shopped online and that the figure would only change slowly over time, as most people still weren't comfortable with computers. I wish we'd bet money on it.

Over a decade later, the book chains all appear to be on the brink of collapse. In the USA, Borders are about to go bankrupt and whilst some commentators have blamed years of mismanagement, the truth is that they have merely accelerated the chain's inevitable demise.

Barnes and Noble had a strong management team and embraced the digital age, but it still wasn't enough. Recently Leonard Riggio, the founder of Barnes and Noble, joked "Sometimes I want to shoot myself in the morning."

On this side of the Atlantic, British Bookshops have just gone bust and the management team of Waterstone's have been congratulating themselves for only losing 0.4% in last year's like for like sales.

On this side of the Atlantic, British Bookshops have just gone bust and the management team of Waterstone's have been congratulating themselves for only losing 0.4% in last year's like for like sales.Given the overall decline in high street sales, -0.4% looks quite promising - certainly much better than its ailing parent company, HMV. But considering that Borders UK ceased trading at the beginning of 2010, it's a pretty dismal result. Waterstone's should have grabbed enough of the Borders market share to come up with some positive figures.

Now that Waterstone's is the last man standing out of the high street bookselling chains, it can only survive by closing its loss-making stores (of which there are a growing number). 20 have already been ear-marked, but I suspect this is only the tip of the iceberg (particularly if HMV are forced to sell the chain).

It's not all bad news for Waterstone's. They still have a significant share of the UK market and there is a core of thriving, profitable stores that have many years left in them if they can free themselves from the shackles of HMV and return to their roots. But overall, I can't help feeling that the age of the chain booksellers was just a brief interlude in the long history of bookselling.

In an article I read recently, someone neatly summed-up the problems facing the bookseller:

The Seven Deadly Paradoxes of Bookselling:

1. The better the bookseller and the more representative their stock, the less chance they have of selling it.

2. The harder a book is to sell, the smaller is their reward for selling it.

3. (The converse, which is more deadly than it first appears.) The easier the book to sell, the greater the reward.

4. The sooner they sell their stock, the longer they must wait before they can replace it on the same terms.

5. In buying the season's new books for stock they must recognize at sight and sometimes at the sight of the jacket only - the merits of their contents.

6. Readers are increasing; purchases are dwindling.

7. The window is their most valuable, and almost their only, advertisement; to be effective it must be in the main part of the town. Few can afford that position.

You may be surprised to learn that these words were written 75 years ago, by Basil Blackwell in a title called "The Book World - a New Survey". Conditions may have changed since 1935 (in Blackwell's day, the enemy was the public library), but the basic principles are the same: sales can rise or fall; rents only go up.

Until recently, it looked as if it was a straightforward battle, with the high street chains losing a war of attrition against the supermarkets and internet booksellers. But just as we were adjusting to the new bookselling landscape, the Kindle suddenly appeared on the scene, shortly followed by the Sony e-Reader.

A couple of years ago I was congratulating myself for swapping high street bookselling for the internet. Little did I know how soon the goalposts were going to move again.

A couple of years ago I was congratulating myself for swapping high street bookselling for the internet. Little did I know how soon the goalposts were going to move again.Keen to reduce their warehousing costs and stay one step ahead of the competition, Amazon have been aggressively promoting the Kindle. When e-books started to appear on Amazon's bestseller charts, they were accused of manipulating the figures to stimulate demand. But according to Jeff Bezos, millions of people now own Kindles and the demand is growing by the day, with Amazon selling around three in every four e-books.

In the UK alone, it is estimated that several hundred thousand people received Kindles for Christmas, so the tipping point has definitely been reached, but where does that leave the rest of the book trade?

This post is all ready far too long, so I'll be brief. Here are, in my opinion, the main issues facing the book trade today:

- The decline of the high street chains will be accelerated by the advent of the e-book. However not all book formats lend themselves to the Kindle, or even the i-Pad. Children's books will contiue to thrive on the printed page, particularly books for young children. Paperback sales will dip sharply, but there will still be a market for titles with high production values. Bricks and mortar booksellers who can adapt to these niche markets stand more chance of surviving.

- If the high street chains collapse, then publishers will find it increasingly harder to develop and promote the next generation of authors. Fewer titles will be published and first-time novelists will struggle more than ever.

- Amazon are taking a risk with the Kindle. If the encoding of e-books is cracked, they could be downloaded and shared as easily as MP3s. If that happens, then publishers, agents, booksellers and authors will see a substantial loss of income.

- With the advent of the i-Pad and its inevitable imitators, why would anyone want to buy a device that only reads books?

BREAKING NEWS... In the three days since I posted this, Borders are trying to negotiate a $500,000,000 refinacing package and Amazon have announced that Kindle sales are now only 20% lower than their paperback sales. Also Waterstone's have asked publishers to reduce scale-down the new title orders and their head of e-commerce has resigned.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

The Age of Certainty

I have resigned from my job as a Waterstone's manager. I have no idea what I'm going to do next, but in spite of this I know that I've made the right decision. I'll miss my friends and I will also miss working with books, but I felt that I had no choice but to leave.

I used to be a manager for Ottakar's Bookstores and loved my job. Under the charismatic leadership of James Heneage, Ottakar's was a wonderful company to work for that valued individuality and creativity over compliance and procedure. As a manager I felt that my remit was to ensure that staff morale was one of the top priorities and I found it really rewarding to see booksellers develop and become managers themselves.

Sadly, in 2006 HMV Media bought Ottakar's and incorporated it into its Waterstone's chain. Within a matter of months every branch of Ottakar's was rebranded and new systems were introduced. I tried to be open-minded about my new employer, but like many of my colleagues, I felt increasingly disillusioned by certain aspects of the business.

It is tempting to write a long, damning diatribe against Waterstone's, but although it might be cathartic to vent my spleen, I would be doing a disservice to the many people who work there who are passionate about books and often do an excellent job against the odds. There are many good things about Waterstone's, but the sum isn't equal to its parts. My own impression is that the company is over-regulated and that there are too many people in middle-management who don't understand the book trade and treat it like any other area of retail, referring to books as product. Bookselling is different.

Perhaps the most succinct and articulate summary of the differences between Ottakar's and Waterstone's was made recently by a former colleague, who wrote:

There seems to be a different definition of what makes a good manager in W - a competent administrator who can follow and implement instructions. O managers were encouraged to focus on running and developing a business. Two different aspects of the same role, but I think many of those who, like you, excel at the latter find nothing satisfying about spending eight hours a day doing the former.

Apparently there is a sea change at Waterstone's. A staff opinion survey revealed that morale was even lower than the senior management feared and this year there will supposedly be a concerted effort to bring back the passion and individuality that made Waterstone's so special in the distant past. The managers I've spoken to certainly seem more optimistic than they have been for a long time. I hope that the senior management have the vision to make real changes rather than cosmetic ones.

If I ran Waterstone's I would scrap at least half of the checklists and reports that are released every week, ensure that a manager's accountability was proportionate to the control they had over their shop and finally, I would make it a sackable offence for anyone to use the acronym JFDI (Just Fucking Do It)!

Between a third and half of Ottakar's managers have left Waterstone's in the last couple of years. Some left straight away, but many decided to see what life was like under Waterstone's before deciding it wasn't for them. Interestingly, in some areas of the country the number of resignations has been lower than a quarter whilst in others it has been well over 50%, which would suggest that the local regional manager has exercised some influence in people's decisions. I have heard some very disturbing allegations, which I won't repeat here.

Financially, Waterstone's is in a stronger position than it has been for years. The latest managing director has introduced many important commercial improvements, including a transactional website and a loyalty card, but it is relatively easy to improve a company that has been poorly managed in the past. The real challenge is to restore that indefinable but vital element that made Ottakar's such a wonderful company to work for: the magic.

I am now unemployed and should be feeling despondent, but in fact I'm happier than I have been for years. I no longer have to lie awake at night worrying about deadlines and targets. I don't have much money but I am free and that feels great. I have also discovered that it's possible to live on very little if you really put your mind to it.

Strangely enough, although I am not working I'm actually busier than ever. In addition to working as a part-time magistrate I have two children to look after, a home to decorate and lots of forms to fill in to prove that I'm not trying to defraud the state. It's a full life.

At some point in the near future I will work again. It may be in the book trade, but I'm also tempted to try something completely different - possibly in the environmental or charity sector. Whatever I end up doing, it will have to be something I feel committed to. Life is too short to spend 40 hours a week doing something you don't enjoy.

In the meantime I have lots of books to read, starting with Tom Hodgkinson's How to be Idle.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)