The entrance to Gibraltar

On a list of places I'd like to vist, Gibraltar ranks slightly lower than Burkina Faso and Wisbech, but when I realised that I'd booked a holiday in Andalucia during the Queen's Diamond Jubilee celebrations, the idea of visiting a British colony was too tempting to resist.

Before I begin, let's get the 'c word' out of the way. Too many people conflate the word 'colony' with 'colonial', which is why territories like Gibraltar and the Falkland Islands are seen as the dying embers of a defunct imperial power. If that was true, they would have been jettisoned with the rest of the British Empire in the late 1950s, but their relationship with the 'mother country' is quite different.

Gibraltar was captured from the Spanish in 1704 and ceded to Britain in perpetuity nine years later, as part of the Treaty of Utrecht. During the next three centuries, the 'Rock' attracted successives waves of immigrants and the Gibraltarians are made up of many different ethnic groups, including British, Spanish, Genoese, Portuguese, Italian, Moroccan, Jewish and Maltese. Today, Gibraltar has a unique identity that is quite different from Spain's, with a history that is almost a century longer than Australia's.

Naturally, Spain isn't terribly happy about having a British colony on their soil and it is viewed as a national humiliation by some. I'd have some sympathy for this viewpoint, but the Spanish objections are rather undermined by the fact that they have a very similar colony on the other side of the Mediterranean, in Morocco.

I also think that regardless of the historical rights and wrongs of colonialism, territorial disputes must defer to the wishes of the current inhabitants and on several occasions, the people of Gibraltar have made it clear that they do not wish to be part of Spain (in 2002, 98.4% of Gibraltarians voted to remain part of Britian).

Perhaps one answer would be to cede part of Britain to Spain - maybe the Isle of Sheppey. I'd welcome the opportunity to enjoy Spanish culture without having to endure the ordeal of EasyJet and I think that the citizens of Sheppey would benefit immensely from the introduction of tapas bars and flamenco dancing.

It was going to be a family trip, but everyone pulled out except our friend Kathryn. "How long do you think you'll be?" my wife asked. I checked the map. Gibraltar was 60 miles away, so it would be a bit like London to Brighton, plus two or three hours to have a look around. "About five hours" I confidently replied.

An hour later, when Kathryn and I found ourselves on a mountain pass with terrifying hairpin bends, courtesy of my SatNav lady, we realised that they journey was going to take a little longer. Kathryn kept apologising for telling me that I was going too near the edge, while I tried to reassure her that I'd rather know.

What were we doing here? At one point, we both wondered if the SatNav had been possessed by an evil spirit.

After an hour of what seemed like aimless wandering, we reached a motoway and started to make up for lost time. Kathryn checked her Rough Guide and saw that it warned against driving into Gibraltar, recommending parking in the Spanish border town of La Linea and crossing on foot. We revised our plans and ignored the increasingly frantic pleas of the SatNav lady.

If you ever get a chance to visit La Linea, don't. It reminded me of all the worst aspects of a Mexican border town - the petty criminals, prostitutes and all-pervading stench of stale urine - without any of the redeeming features. Worst of all, because the Spanish don't like to officially acknowledge the existence of Gibraltar, they won't tell you where it is. We spent a miserable half hour in La Linea before we finally stumbled across the border.

By the time we passed through customs (during which a bored official pretended he hadn't seen us), a thick mist had descended. Kathryn looked around her and said "God, even the weather's British."

Arriving was a huge culture shock. On the one hand it was all terribly familiar, from the red telephone boxes to the London Transport font on the local buses, but the setting - a blend of 1960s Malta, Ceausescu's Bucharest and Littlehampton - was deeply unsettling. I felt as if I was in an episode of 'The Prisoner'.

We boarded a bus and began a ridiculously long and convulted journey that belied Gibraltar's three-mile length, passing a succession of bland concrete apartment blocks, whose windows were festooned with Union Jacks. It made the muted displays in Lewes look positively Calvinst.

Two buses and nearly an hour later, we reached the bottom of the Rock of Gibraltar, where a cable car shuttled visitors to the 1,400ft high summit. I'd never been in a cable car before and kept thinking of 'Moonraker'.

Travelling in a small metal box suspended on a piece of string is not for the faint-hearted and I carefully scrutinised the cable for signs of metal fatigue, whilst Kathryn sat on the floor. However, as the car climbed above the clouds, we were rewarded with a stunning view, with the coastline of Africa in the distance:

But for me, the real attraction of the Rock was the colony of Barbary Macaques - Europe's only native apes:

The macaques seemed completely indifferent to the humans who visit their territory, although they apparently like snatching cameras and throwing them into the sea. Wise creatures.

You can sit right next to an ape and they won't move. Some visitors have mistaken indifference with tameness and been rewarded with a nasty bite.

According to popular myth, Gibraltar will only remain British as long as the apes live there. Winston Churchill was susperstitious enough to augment their population with some Moroccan cousins during the Second World War.

Meanwhile, back in the town, the Jubilee fever was hotting up:

We decided that walking back to La Linea would be quicker than travelling by bus and as we aproached the centre of Gibraltar, I looked forward to seeing the colony's thriving commercial quarter:

Gibraltar is an internationally-renowned tax haven, but this hadn't saved it from the long reach of the global recession. I saw a number of empty stores - most of them clothes shops. Only Marks and Spencer appeared to be thriving, which explains why so many women were wearing

Per Una.

The heart of Gibraltar is a pleasant mixture of 18th and 19th century stone buildings - Lyme Regis with a Mediterranean twist - and if we'd had more time, I would have liked to explore the narrow alleys. But it was getting late and my wife's texts sounded increasingly desperate.

We walked back to the border, where a single British bobby looked out for international drug gangs and illegal imigrants, in between posing for photographs with German tourists. The Spanish customs official didn't even look up from his computer screen.

On the Spanish side of the border

At the underground car par in La Linea, I programmed a new, direct route on the SatNav. It had been an exhausting day and I couldn't face any more mountain passes. Within minutes we were on a motorway, speeding back to my distraught family. Kathryn texted my wife to say that we'd be home within the hour.

Then it happened again: "After 500 yards, take the next turning on the right" and before we knew it, we were back on a road that was barely wider than the car, negotiating bends that made Grand Theft Auto look like

Genevieve. My heart sank.

By the time we reached another main road we were already three hours late and the sun was beginning to set. But just as Kathryn and I were beginning to lose heart, our road met the coastline and I caught a glimpse of Africa on the other side of the water, so close that you could see houses and boats.

I thought it was wonderful, but Kathryn had had enough: "Oh, fuck Africa".

It was almost dark when we arrived at our house in Los Caños de Meca. My wife's irritation at being left alone for so long had turned into a relief that we had finally made it back. "How was Gibraltar?" she asked.

I quoted Dr Johnson's verdict on Fingal's Cave: "Worth seeing, but not worth going to see".

Before I bluffed my way into the world of secondhand bookselling, I naively assumed that the older a book was, the more valuable it might be.

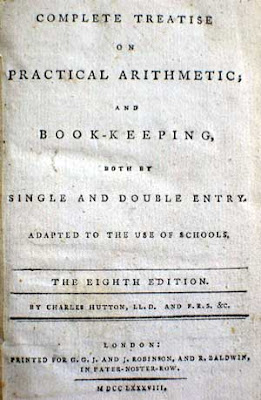

Before I bluffed my way into the world of secondhand bookselling, I naively assumed that the older a book was, the more valuable it might be. Perhaps it's even the book in Gainsborough's portrait, although I think it's highly unlikely that David Garrick would have owned a copy of this:

Perhaps it's even the book in Gainsborough's portrait, although I think it's highly unlikely that David Garrick would have owned a copy of this: It sounds terribly dull, but in fact it's a box of delights, giving the reader a fascinating glimpse of late 18th-century society:

It sounds terribly dull, but in fact it's a box of delights, giving the reader a fascinating glimpse of late 18th-century society: Over 6lb of opium? Nancy Reagan would be spinning in her grave (but apparently she's still alive).

Over 6lb of opium? Nancy Reagan would be spinning in her grave (but apparently she's still alive). In fact, whenever I find a very old textbook, I feel humbled by its complexity. If I was transported back to a 1788 classroom, I'd be the one in the corner wearing a dunce's hat.

In fact, whenever I find a very old textbook, I feel humbled by its complexity. If I was transported back to a 1788 classroom, I'd be the one in the corner wearing a dunce's hat.