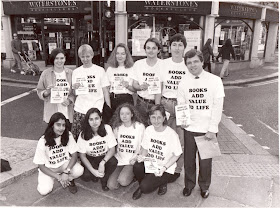

When I joined Waterstone's, over 20 years ago, I was told that one of my jobs would involve buying new titles from publishers. Surprisingly, there was no training, but in spite of this I was given a monthly budget of £5000 to spend in any way I pleased. Unsurprisingly, when the word got out that Waterstone's had delegated its new title buying to a load of chinless wonders, it was like a feeding frenzy.

When I joined Waterstone's, over 20 years ago, I was told that one of my jobs would involve buying new titles from publishers. Surprisingly, there was no training, but in spite of this I was given a monthly budget of £5000 to spend in any way I pleased. Unsurprisingly, when the word got out that Waterstone's had delegated its new title buying to a load of chinless wonders, it was like a feeding frenzy.One of the first things that impressed me was how many sales reps there were. HarperCollins alone had four, just for SW London (one for fiction, another for children's, one for general non-fiction, plus a dedicated rep for maps and reference), whilst most of the other major publishers had at least two.

If you only had one sales representative per region, you weren't a proper publisher.

As a result, I probably spent around 60% of my time buying new titles from sales reps, during meetings that were called 'subbing' sessions. Until I reached the dizzy heights of management, all new title buying had to take place on the shop floor, so we usually tucked ourselves away in a quiet corner where we wouldn't be bothered by customers.

Each representative turned up with at least one large suitcase containing huge files of blad (which stands for book layout and design), showing mock-ups of dustjackets, blurbs and details of how much publicity the book was going to get. My job was to decide whether the book would sell in Richmond and, if I thought it would, guess how many copies we'd need.

Initially, I had no idea what I was talking about and the whole buying process seemed farcical. Some reps saw a golden opportunity for a stitch-up, convincing me that an obscure £35 book on dolphins warranted a minimum order of five copies. The more experienced reps took a longer view, knowing that any duds would only come back as returns, which would have to be credited back to the bookseller.

Initially, I had no idea what I was talking about and the whole buying process seemed farcical. Some reps saw a golden opportunity for a stitch-up, convincing me that an obscure £35 book on dolphins warranted a minimum order of five copies. The more experienced reps took a longer view, knowing that any duds would only come back as returns, which would have to be credited back to the bookseller.The best reps effectively taught me how to do my job, gently nudging me in the right direction if I'd overestimated how many books we needed. I had the good sense to listen to them, but not everyone did. When one young bookseller stubbornly refused to accept that he needed five rather than 40 copies of a new poetry title, the rep slammed his folder shut and said "Look, I'm going to go away now. I'll come back when I can talk to a grown-up."

The second thing that impressed me about the reps was how few of them read books. You would imagine that if a publisher employed people to sell its titles, they would try to recruit bookish, literary types. However, the majority of the 'old school' reps had no interest in books and would have been just as happy selling exhaust pipes or photocopiers.

There seemed to be very strong class divisions in the traditional publishing world. The public school, university-educated types went into the editorial departments, whilst the vulgar business of actually selling the books was left to people who had mostly left school at 16.

At first it seemed absurd that publishers had a sales force made up of people who didn't know that George Eliot was a woman, but over time I came to realise that the best sales reps were frequently the Brians and Barrys, who didn't read, whilst the worst were often the bright young things who may have had English degrees, but didn't know how to sell a book.

In the early 1990s, the typical rep was a man in his mid 50s, with a bald head, moustache and a ruddy face that indicated an approaching heart attack. I lost count of the number of times I heard the phrase "Keith won't be in for a while - he's just had a heart attack" (I suppose it was all those 'Little Chef' meals). When he arrived, panting with the effort of dragging a suitcase from the car park, I never knew whether he'd make it to the end of the session.

Keith may not have been widely read, but he knew his market. He understood that X sold well in Windsor but not in Slough, whilst Y was unknown outside the M25. Sadly, the editorial departments rarely seemed to take of notice of their reps' sales reports and a large part of our buying session would be spent moaning about our respective head offices.

Keith may not have been widely read, but he knew his market. He understood that X sold well in Windsor but not in Slough, whilst Y was unknown outside the M25. Sadly, the editorial departments rarely seemed to take of notice of their reps' sales reports and a large part of our buying session would be spent moaning about our respective head offices. "Honestly Phil, you tell me, how am I going to sell this? They haven't got a clue."

It was a working-class, male-dominated world. Hours were spent on the road, so the car was king and each rep knew every service station and shortcut. If you wanted to get rid of a rep, giving them an Austin Montego was usually enough.

Some of the reps had little scams that made them feel that they were getting the upper hand over their unsympathetic employers. For example, when one rep went to get petrol, his wife followed him in her car and filled her tank during the same sesion (when someone challenged the rep about his fuel costs, he brazened it out: "It's a thirsty car mate").

Some of the reps had little scams that made them feel that they were getting the upper hand over their unsympathetic employers. For example, when one rep went to get petrol, his wife followed him in her car and filled her tank during the same sesion (when someone challenged the rep about his fuel costs, he brazened it out: "It's a thirsty car mate").Occasionally, a bright young thing at head office would try to get the reps more engaged with the titles they were representing:

"Phil, I got this fucking memo from some tosser at Head Office telling me I had to read this new novel and write a report about it! D'you know what I did? I phoned him up and said I haven't read a fucking book in 25 years and I'm not going to start now."

But not all of the reps were 'wide boys'. One was an ex-public school man in his 60s, who lived in an expensive London flat with his belligerent, alcoholic mother. In spite of his effete manner and Brian Sewell voice, he was at pains to let us know that he was heterosexual, constantly praising the feminine charms of detox guru Leslie Kenton:

When it came to Alan Hollinghurst, he was less enthusiastic:

"This is a book by a homosexual author that will only be of interest to other homosexuals".

He wasn't terribly keen on Irvine Welsh either:

"Here is another book for young people to waste their pocket money on".

It was all said with a faint twinkle in the eye, but I felt that he was a rather bitter, disappointed man, trapped in a world he despised. When he was forced to retire, he refused to accept the gold-plated fountain pen that his colleagues had bought for him.

But by the time I became a bookseller, the traditional reps' world was changing. The Keiths were increasingly being replaced, either by Sues (much to the relief of many female booksellers) or earnest young graduates and the subbing sessions - once a mixture of dirty jokes, gossip and moaning - became more businesslike in tone.

Overall I got on very well with the sales reps and came to regard some of them as friends. They were generally bright, funny people with a healthy cynicism about the publishing industry and, most important of all, a good sense of humour. When I left high-street bookselling, one of the things I really missed was having a good gossip with a rep.

I loved exchanging scurrilous anecdotes about colleagues. I learned that one Ottakar's manager regularly had pyjama-party sleepovers in her shop, whilst another had stolen enough money to buy a sports car (he ended up in prison). But my favourite gossip was about authors. I learned that Jilly Cooper was lovely but Jeffrey Archer was deeply unpleasant, whilst Terry Pratchett could be very grumpy, only turning on the charm for his fans.

If a sales rep had ever been treated badly by an author, we all knew about it. In a few cases, an author's career was effectively killed off by the rep, as we all conspired to make sure that their books were barely visible.

The rep's job has got a lot harder in recent years. Every year, redundancies and early retirement have trimmed the sales forces of publishers and the surviving reps have been expected to cover ever larger areas for little or no extra pay. The once ubiquitous HarperCollins rep is now as elusive as the natterjack toad.

With only one major book chain left, the age of the publisher's rep is almost over. I think that there should be a memorial coat of arms, depicting a full English breakfast, some blood pressure tablets and a large black suitcase on wheels. But sadly, I think their passing will be unnoticed by all but a few.